Shamanism

The word ‘shaman’ comes from one of the original tribes from Siberia. Whenever a community faced illness or serious problems the people called upon their shamans: men and women who were able to contact the spirit world. Each shaman had his or her own spirit helpers who would offer assistance during healing rituals, who could give advice that would help to solve problems and who helped the shaman to guide the souls of the dead into the world of the ancestors. The various Siberian tribes had their own customs and mythology so there were considerable differences between the shamans of different regions. Still, there were enough similarities between them all to justify the use of the term ‘Siberian shamanism’.

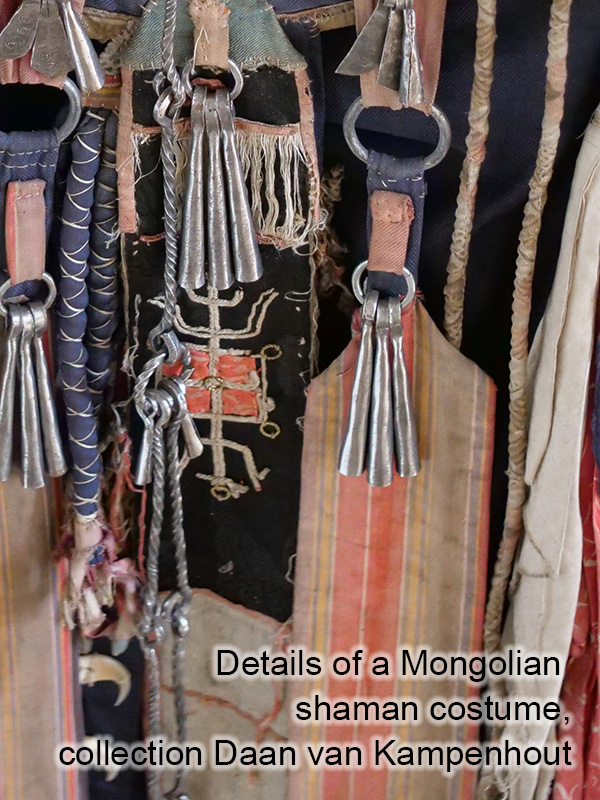

Siberian shamanism was not only found in Siberia proper but also in the areas at its southern and southeastern borders. In the north of China there are shamanic nomadic groups who are closely related to their Siberian neighbors. In the most northern islands of Japan live the shamanic Ainu. In Mongolia (Siberian) shamanism and (Tibetan) Buddhism have existed independently but were also sometimes mixed. There, the Buryat, Darkhat and several other tribes had their own shamans. One of the characteristics of Siberian shamanism is that most shamans used special ritual costumes on which images of the spirit helpers were attached. The Sakha/Yakut shamans of central Siberia had up to two hundred iron pendants and images attached to their leather coats. The Tofalar and Soyot shamans from southern Siberia used only few iron hangers but attached hundreds of textile snakes and ribbons to their costumes. Shamans of the Evenki, Dolgan and Altai combined quantities of iron and textile, sometimes adding decorations of small beads and shells. Whatever material was used to make a shaman costume, a shaman costume could easily weigh ten or fifteen kilos.

Beside a special costume, Siberian shamans used big flat drums. The shamans of tribes such as Nanai and Udeghe did not wear elaborate shaman costumes during their ceremonies, but they also would use the characteristic large flat drums. A shaman would beat the drum in a monotonous rhythm and sing long songs to invite the spirits. In some tribes the shamans would improvise words and melodies, in others they would mainly sing old traditional songs. Invited by the songs the helping spirits and ancestors would gather around the shaman. The shaman would dance, and would soon be exhausted by the weight of the heavy costume and drum. Tiredness helps to enter and deepen the trance state. When the shaman was fully in trance and had his/her spirit helpers available the real work could begin. The shaman would seek out the spirits that caused illness and problems, and through communication with them would try to find healing or solutions.

Classical Siberian shamanism became more or less extinct in the 20th Century. Soon after the revolution of 1917 a campaign was launched to convince the Siberian tribes that they should to avoid the shamans and no longer should ask them for their help. Under Stalin the remaining practicing shamans were either killed or imprisoned in the camps of the Gulag. Nowadays there are only very few shamans left who are directly linked to the old traditions. On the material level very few objects remain: in museums and private collections one can still see some original old shaman costumes, drums and other ritual objects. After the decline of communism, there are people in some parts of Siberia who turn once more to shamanism. There are various folkloristic groups whose members sing old shaman songs while dressed in costumes resembling the traditional shaman’s clothes. There are also individuals who have picked up the shaman’s work again. Most of these people are however not traditional shamans, often they are recreating half forgotten shamanic practices. Only few of them are directly linked to the traditional shamans of earlier times.

People in the western world learned about the shamans in the eighteenth century through travel rapports written by people who explored Siberia. For a long time only the academic world had some knowledge about the shamans, but in the seventies of the twentieth century shamanic practice started to become known as a popular spiritual path, mostly influenced by native American teachers. At that time, the books of Carlos Castaneda generated a lot of interest in shamanism. In the late seventies Michael Harner developed a method that enabled westerners to experience the basic steps of shamanic trance for the first time in a workshop format.

A westerner interested in shamanism can now choose from all kinds and styles of shamanic work. Very few western practitioners are using shaman costumes, but drums are used by practically all of them. The art of journeying to and through the world of helping spirits and ancestors is commonly practiced. Contemporary shamanism has adopted several elements from the Native American traditions: many people know the wheel of the four directions and/or participate in sweat lodge ceremonies. Some practices from the Latin American shamanic traditions, like the ayahuasca ceremony, have also become widely available in the west. Additionally, various wester shamanic practitioners are looking at the pre-Christian roots of their cultures, and they are finding shamanic elements there. New techniques and rituals are based on these finds. Shamanism has never completely died out, some people kept the traditions (or parts of them) alive even in times of brutal suppression. Shamanism continues to renew itself.